A guest post by Laura Macaluso

Virginia is a state (technically a “commonwealth”) with a unique pedigree in American history. The site of the first permanent English settlement (Jamestown, 1607), Virginia can claim several things: more American presidents come from here than any other place; its historic houses are among the most visited in the country (Mount Vernon, Montpelier and Monticello among them); and the capital of the Confederate States of America was here (Richmond, mostly) as is Arlington National Cemetery, created out of Robert E. Lee’s home and property.

It’s no wonder that among these many events that literally changed the course of history, there are hundreds if not thousands more stories rising up out of the ruins of what used to be a singular version of American history. The 20th century, with its world wars, nationalistic narrative and eventual heaving social changes, is no more—the 21st century is about inclusive history: history told from the “bottom up” with emphasis on people heretofore neglected in mainstream history books. Further, the practice of public history places the research and writing and sharing of history in the hands of anyone who wants to participate. Public history is done far away from the Ivory Tower, and strives to connect the past to the present.

A recent headline-grabbing story from the ashes of American history is undergoing such treatment. It is the history of Nat Turner, known to most as the name in “Nat Turner’s Insurrection,” but unknown to most as a husband, father, and preacher, who was enslaved on plantations in Virginia.

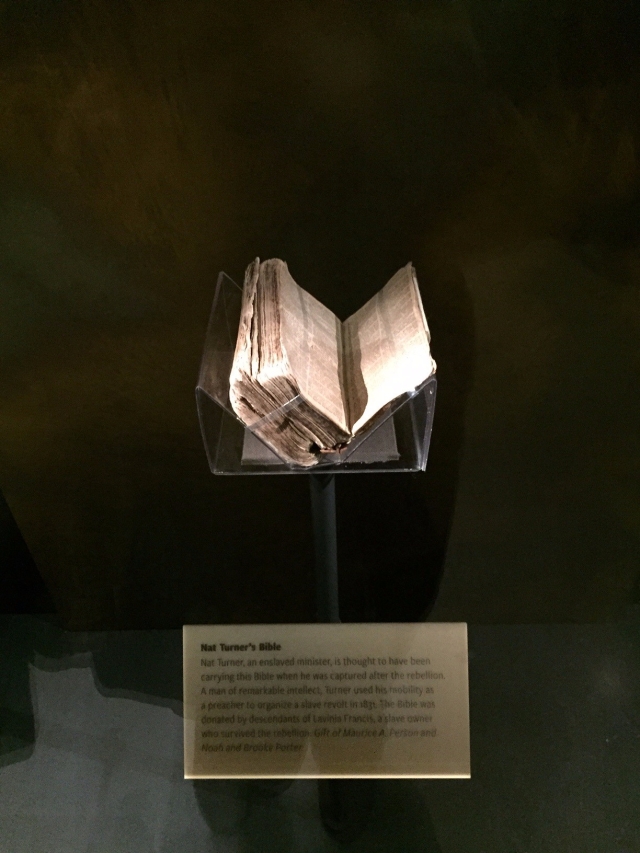

Nat Turner’s Bible, National Museum of African-American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution. Photograph by the author.

Thanks to the efforts of Kelley Fanto Deetz, a historian, archaeologist and facilitator, the story of Nat Turner is getting the attention it deserves, so that Turner’s whole story is told—pushing aside the common practice of whittling history down to a few words, such as “Rebel” or “Murderer” that have dictated his narrative for generations.

Deetz has a long background in the study of African and the African-American diaspora. Although she is the daughter of a well-known American anthropologist (James Deetz, 1930—2000, author of In Small Things Forgotten: The Archaeology of Early American Life) Deetz did not see herself becoming an academic when she was younger. But, as it happens, Deetz fell in love with the study of black culture, and studied at prestigious schools, getting her bachelor’s from the College of William and Mary, and then master’s and doctorate from the University of California, Berkeley. Because of her work on Nate Parker’s film Birth of a Nation (2016), Deetz became involved with Nat Turner’s story—determined to track down historical documentation to support the rehabilitation of Turner’s reasons for leading a revolt in which 70 enslaved men killed at least 55 white slave-holding families in Southampton County, Virginia in 1831. In this work, Deetz is working hard to reframe the Turner story, and to point out the questions we should have been asking all along.

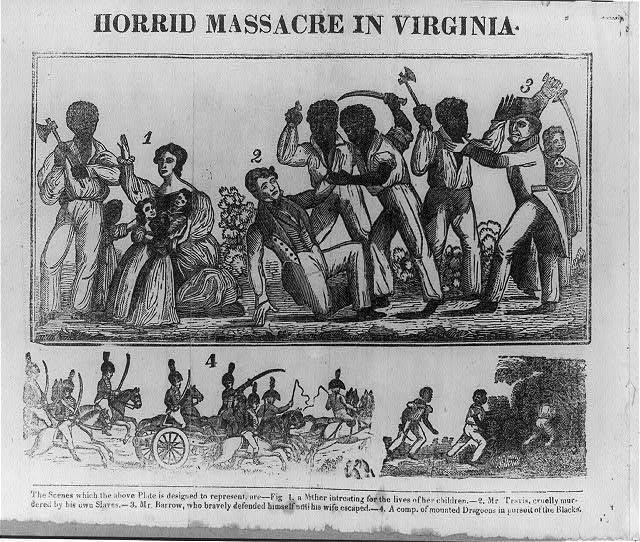

Turner’s revolt led to his own hanging, but, so too were many innocent African-Americans punished in retaliation for the murders. Although Turner was painted a martyr by some, African-Americans did not have the opportunity to participate in the writing of mainstream American history books. Thus, Turner became a rebel, codified in newspapers, books and artwork as the instigator of the “Horrid Massacre in Virginia.”

Horrid Massacre in Virginia, unknown artist, circa 1831, Library of Congress.

And, indeed, the evening and early morning hours of August 21-22, 1831, must have been horrid, but, Deetz makes a strong point when she asks her audience, “Why should Turner be labeled a rebel when what he wanted was his freedom?” Highlighting the contradiction of Americans proudly remembering the revolutionaries of independence from Britain, but refusal to identify and label Turner and the men who accompanied him with the same understanding, it’s another example in a long line of many, in which white Americans distance themselves from African-American “agency” (which is the power to make decisions for yourself and act on it) and worse, sanction the brutalizing of black people, young and old, male and female.

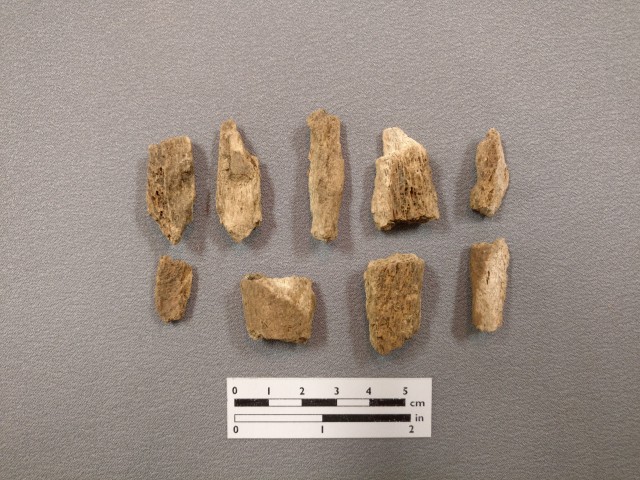

An example of the ways in which white Americans were able to distance themselves from the humanity of African-Americans is summed up in the bones of Nat Turner: after his hanging, Turner’s body was dismembered, with the skull, skin and other bones going to various places and used in different ways, each more awful than the next—stories of which resemble the atrocities committed by the Nazis one hundred years later (his skin was apparently made into a coin purse and a lampshade, for example).

Bone fragments found at the suspected burial site of Nat Turner and others in Southampton County, Virginia. Courtesy of Kelley Fanto Deetz.

Deetz plans to continue archaeological work at a site in Southampton County where bone fragments were found last September. There is much more to do, but Deetz’s work has garnered the attention of National Geographic and will influence the way in which Nat Turner and his revolutionaries are re-remembered in American society.

For further reading, see:

Article, Kelley Fanto Deetz, “The Bones of Nat Turner, Reclaiming an American Rebel,” National Geographic History, January/February 2017: 74-89 and https://thesharedhistoryproject.org/.

Film, The Birth of a Nation, Nate Parker (director), 2016.

About the Author

Laura A. Macaluso, Ph.D. has degrees in art history and the humanities from Southern Connecticut State University, Syracuse University in Italy and Salve Regina University. Her most recent book is New Haven in World War I (The History Press, 2017), endorsed by the World War I Centennial Commission.